Need to Improve Your Transportation Plans? Try Inverting the Order of Planning

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

Are your transportation plans letting you down? Regions everywhere have adopted ambitious goals for their long-range plans, from climate change to land use to reductions in automotive dependency. Yet even with decades of spending on creating new transit and bicycle infrastructure, many cities still struggle to see the kinds of changes in their travel and growth patterns that point in the direction of resilience and sustainability.

Covid-19 has highlighted these issues, upending travel patterns and choices, with what may be permanent reductions in office commuting, as well as big impacts on transit and shared ride services. At the same time, Covid has created a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rethink our use of public space, much of which has been dedicated to automotive movement (roads) and storage (parking).

Transportation planning can lead to better outcomes by focusing on three parallel strategies:

- Identify what solutions look like

- Invert the order of planning

- Update your computerized planning models

1. Identifying Solutions

Too often, transportation projects are pushed through with no clear sense of whether or not they will be able to solve the problems for which they are intended. Planners and politicians jump to efficiency and expansion before effectiveness can ever be established.

Once planners learn how to produce a desired solution, they can then engage in value engineering by asking how they can achieve desired results more efficiently. A perfect example of this is Curitiba, Brazil, famed as one of the innovators of Bus Rapid Transit (BRT).

Curitiba didn’t set out to develop a BRT system. What they did was identify, up-front, what their ideal transit network should look like. In their case, it was a subway (metro) system with five arms radiating out of their downtown and s set of concentric ring routes surrounding the center.

Curitiba’s “solution” to creating an effective transit network was based on five major corridors radiating from their downtown and a set of concentric rings linking major transfer stations (“Integration Terminals”).

Subways are incredibly expensive to build. So Curitiba’s leaders asked themselves how they could replicate the functionality of their ideal network as quickly as possible with available resources. They decided to create their ideal subway system on the surface, running extra-long buses along dedicated transitways in the centers of their major roads. Enclosed stations with level boarding were spaced every 500 meters (three to a mile). Major “integration terminals,” about every 2-3 km apart, serve “Surface Subway” lines, an extensive regional express network, and local buses. They also feature government services, recreation centers, shops and eateries.

This transit corridor in Curitiba features a dedicated center-running busway with auto traffic and parking relegated to the sides of the boulevard and to parallel roads.

Besides moving passenger loads normally associated with rail systems, the strategy was tied to a land use plan that placed most of the region’s denser land uses within one block of surface subway lines. Use of transit for commuting rose from about 7% in the early 1970s to over 70% by the 2000s. As a look at the skyline of Curitba reveals, the city literally and conspicuously developed around its transit network.

By restricting high densities to “surface subway” corridors, Curitiba literally grew around its transit system. Besides preserving more land for single-family homes, this strategy reduced the impacts of new growth substantially.

2. Invert the Order of Planning

The order of planning reflects the priority assigned to different modes as solutions to your goals. It is fair to say that most regional strategies today embrace the importance of modes such as transit and bicycling, yet this is rarely reflected in the order of planning.

Most cities begin or center their transportation planning by focusing on optimizing their automotive systems: expanding capacity, improving signaling, building new roads, often dictated by where road congestion is at its worst. The logic is impeccable: the auto is the primary mover of people, and too many new transit and bicycle projects have only shifted a relatively small number of trips, highlighting popular preferences.

Once the automotive system is optimized, transit planning is then asked to fit around the automobile. In most places, transit either shares the right of way with cars, or is delayed by traffic signals and cross traffic. In some cases, corridors are identified which could support rail or BRT infrastructure. Pedestrian circulation is then asked to fit around car traffic and transit. Finally, the bicycle is asked to fit around everything else.

This bicycle lane along an 80 kph (50 mph) expressway in California puts cyclists at great risk from distracted drivers.

The alternative is to engage in Advanced Urban Visioning, a process that identifies what optimized or ideal systems look like, much like Curitiba did decades ago. You get there by inverting the order of planning. You begin with transit, allowing an ideal network to emerge from a detailed analysis of urban form (how your region is laid out), and trip patterns. An optimized transit system is one that focuses on three key dimensions: network structure (how you connect places), system performance (how long it takes to get from origins to destinations), and customer experience (essentially, what a person feels and perceives as they move through the system). The goal is to connect more people more directly to more likely destinations in less time, with an experience that makes them feel good about their choice of transit.

The transit network at this point is still diagrammatic; a set of nodes and links more than a set of physical routes. Even so, it likely looks little like your current transit plan.

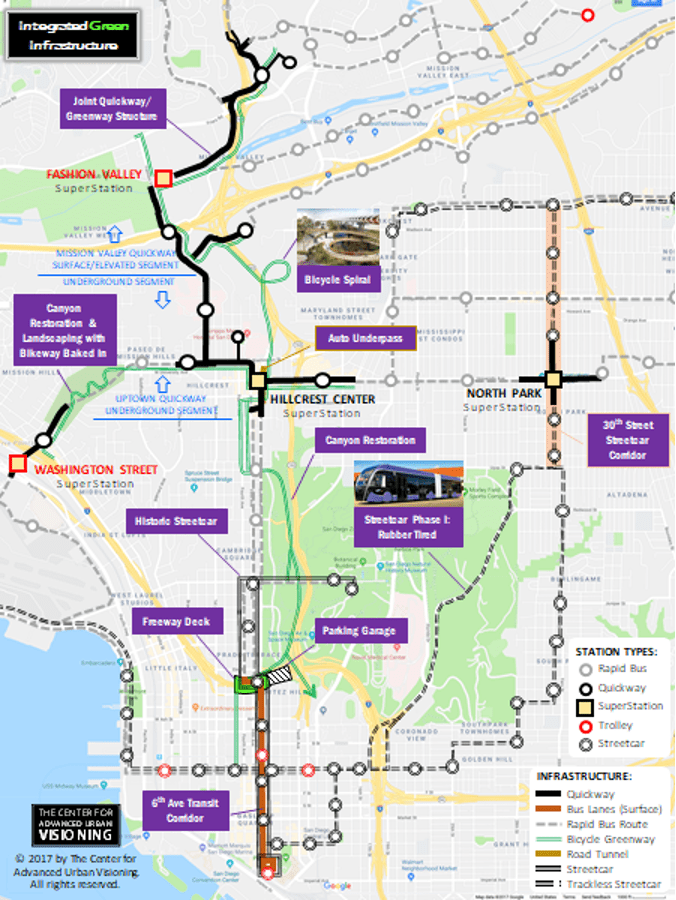

This aerial of central San Diego shows many of the principal nodes of the zone and the likely connections between and among them. The rapid transit map, meanwhile, looks little like this network.

Why does transit go first?

To begin with, transit often requires heavy infrastructure, be it tracks, transitways, bus lanes, stations, or garages. Stations, in particular, need to be located where they will do the most good; even short distances in the wrong direction can make a big difference in public uptake of transit. Second, transit otherwise takes up relatively little urban space when compared to the car. For example, there are two-lane busways in Australia that move as many people during the peak hour as a 20-lane freeway would move. Third, transit, when well-matched to a region, can significantly shape how that city grows, as access to a useful transit network becomes highly valued.

Getting from an idealized transit network to an actual plan happens through a staging plan that focuses on “colonizing” whatever existing road infrastructure is needed, and specifying new infrastructure where necessary to meet strategic goals. In practice, this means identifying locations where new transitways, surface or grade-separated (free of cross-traffic or pedestrian crossings), can meet performance and connectivity goals. Planners also need to devise routes that minimize travel time and transfers for core commuting trips. Transit at this stage is free to take space from the auto, where warranted; to meet performance goals subject to expected demand.

Brisbane, Australia’s, Busway system includes many grade-separations (bridges and tunnels) so that buses can operate unimpeded by traffic.

Once an optimized transit plan is identified, the next step in Advanced Urban Visioning is to develop an idealized bicycle network. Drawing on the lessons of the Netherlands, perhaps the global leader when it comes to effective bicycle infrastructure, this network is designed and optimized to provide a coherent, direct, safe, and easy-to-use set of separated bikeways designed to minimize conflicts with moving vehicles and pedestrians. This approach is a far cry from the piecemeal incrementalism of many cities. It also gives the bicycle priority over cars when allocating space in public rights of way.

Amsterdam and other Dutch cities have some of the best-developed bicycle infrastructure in the world, providing cyclists with an extensive network of separated bike lanes.

The third step in Advanced Urban Visioning is to use major transit nodes to create new “people space”: walking paths, public plazas, parklands, and open space trail networks. These may colonize land currently occupied with motor vehicles. These new spaces and parklands may also be used to organize transit-oriented development; the combination of optimized transit and bicycle networks, and park access can increase the value of such development.

In this example, from a conceptual plan developed for San Diego, a “Strategic Investment Zone” (SIZ), supporting high-density residential and commercial uses, wraps around a linear park and two proposed community parks. The proposed underground transit and surface parks together add significant value to the SIZ, some of which may be captured through an Infrastructure Finance District mechanism to help fund much of the project.

Only after transit, bicycles, and pedestrians are accommodated is it time to optimize the automotive realm. But something happens when these alternative modes are optimized to the point that they are easy, convenient, and time-competitive with driving: large numbers of people shift from personal vehicles to these other travel modes. As a result, the auto is no longer needed to move large numbers of people to denser nodes, and investments in roadways and parking shift to other projects.

The power of Advanced Urban Visioning is that it gives you clear targets to aim at so that actual projects can stage their way to the ultimate vision, creating synergies that amplify the impacts of each successive stage. It turns the planning process into a strategic process, and helps avoid expensive projects that are appealing on one level but ultimately unable to deliver the results we need from our investments in infrastructure.

“San Diego Connected,” a conceptual plan developed at the request of the Hillcrest business community, demonstrates Advanced Urban Visioning in action, combining bicycle, transit, pedestrian, and automotive improvements that optimize their potential contribution to the region.

Advanced Urban Visioning doesn’t conflict with government-required planning processes; it precedes them. For example, the AUV process may identify the need for specialized infrastructure in a corridor, while the Alternatives Analysis process can now be used to determine the time-frame where such infrastructure becomes necessary given its role in a network.

3. Update Your Models

For Advanced Urban Visioning to make its greatest contribution to regions, analysis tools need to measure and properly account for truly optimized systems. Most regional agencies maintain detailed Regional Travel Models which are computer simulations of how people get around and the tradeoffs they make when considering modes. Many of these models work against Advanced Urban Visioning. The models are designed generally to test responsiveness to modest or incremental changes in a transportation network, but they are much weaker at understanding consumer response to very different networks or systems.

Regions can sharpen the ability of their models to project use of alternative modes by committing to a range of improvements:

- Incorporate market segmentation. Not all people share the same values. Market segmentation can help identify who is most likely to respond to different dimensions of service.

- Better understand walking. Some models now include measures as of quality of the walking environment. For example, shopping mall developers have long known that the same customer who would balk at walking more than 150 meters to get from their parked car to a mall entrance, will happily walk 400 meters once inside to get to their destination. Likewise, people are not willing to walk as far at the destination end of a trip as they are at the origin end, yet most models don’t account for this difference.

- Better measure walking distance. Not only do most models not account for differences in people’s disposition to walk to access transit, they don’t even bother to measure the actual distances.

- Better account for station environment and micro-location. We know from market research that many people are far more willing to use transit if it involves waiting at a well-designed station, as opposed to a more typical bus stop on the side of a busy road.

- Incorporate comparative door-to-door travel times. No model I am aware of includes comparative door-to-door travel time (alternative mode vs. driving), yet research has continually demonstrated the importance of overall trip time to potential users of competing modes.

Conclusion

Advanced Urban Visioning offers a powerful tool for regions that are serious about achieving a major transformation in their sustainability and resilience. By clarifying what optimal transportation networks look like for a region, it can give planners and the public a better idea of what is possible. It inverts the traditional order of planning, ensuring that each mode can make the greatest possible contribution toward achieving future goals.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

It’s great to see Alan’s ideas here. He is a national treasure. If I was the newly elected President Biden, Alan would be my first hire for mobility. These are all great ideas in this article. We have to do better, and we need our public transit agencies, MPOs and other government agencies focused on the kind of innovation Alan is discussing here.

I have picked great ideas for transport planning in rapidly growing cities in Kenya experiencing mobility challenges. Visionary planning.