The Case Against Freeway Expansion

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

No one likes to sit in “soul crushing” traffic; they call it “soul crushing” for a reason. People move because of traffic. They decide not to take jobs or leave the jobs they have because of traffic. It’s not only bad for blood pressure, it’s also bad for the health of a city. More traffic means more global warming emissions and more air pollution that worsens asthma and causes heart and lung disease. It means wasted hours and lost productivity (and money) for local businesses.

For all these reasons (and more), it’s no wonder cities across the country are looking for ways to alleviate traffic. But does the traditional go-to solution of expanding freeway capacity actually help?

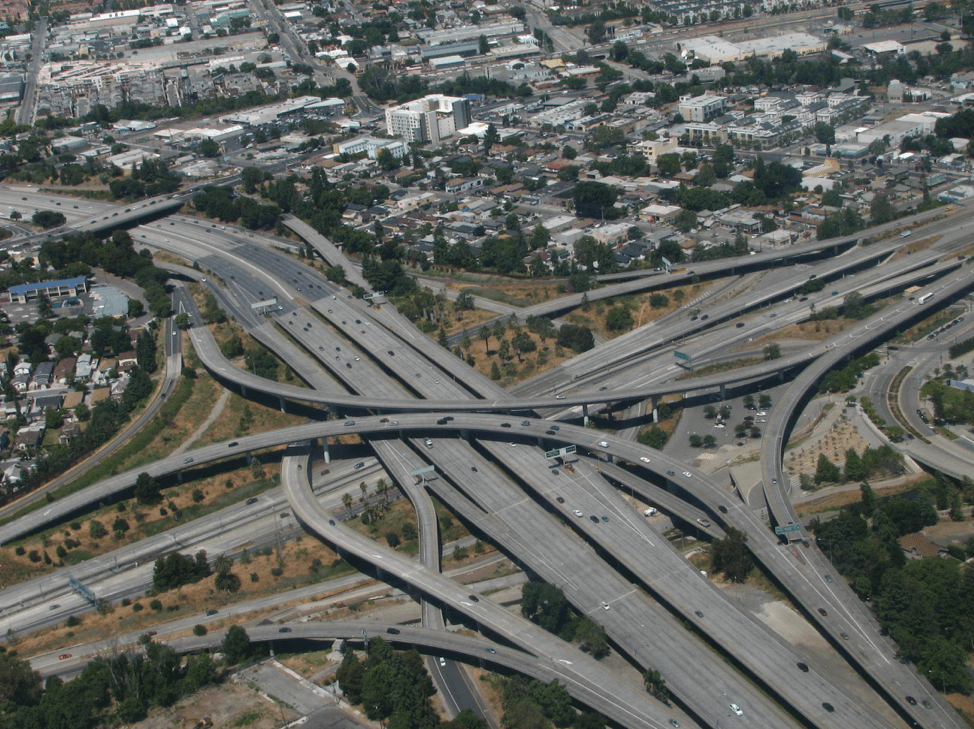

Cities across the country are spending billions of dollars to lay new pavement. But does it actually help solve any of our transportation problems? Image: Wikimedia Commons.

The Problem with Freeway Expansion

Expanding an urban freeway is an expensive way not to solve a problem. Time and time again, we’ve seen that when cities add urban freeway capacity, it results in more freeway travel and doesn’t reduce congestion. And yet, states are still spending billions of dollars doing it.

When you widen a highway, you set off a chain reaction of societal decisions that ultimately, and oftentimes quickly, brings you back to a congested highway. Businesses might decide to move or build new locations on the outskirts of the city in order to take advantage of the new highway; residents may choose to move farther away in pursuit of cheaper housing; commuters who had been leaving earlier for work in order to avoid traffic might travel at rush hour once again; those who had been taking public transit might get back into their cars.

This phenomenon, called “induced travel” or “induced demand,” takes up additional space on highways, and is so predictable that it has been called the “Fundamental Law of Road Congestion.”

With transportation emissions now the number one contributor to global warming, we must promote low-carbon forms of transportation wherever possible. Highway expansion does just the opposite.

Freeway expansion can also cause irreparable harm to communities: forcing the relocation of homes and businesses, widening “dead zones” alongside highways where street life is unpleasant or impossible, creating barriers between neighborhoods, reducing the city’s base of taxable property, and creating noise and pollution that degrades quality of life.

To Build or Not To Build: Tampa vs. Seattle

In 2016, the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) was moving forward with a $3.3 billion plan for new toll lanes to let drivers bypass congested traffic on I-275, I-75, and I-4 in Tampa. The project was moving forward despite FDOT’s acknowledgement that it would not solve the region’s congestion problems.

Aside from being expensive and unnecessary, the new project would also cut through the community of Tampa Heights, destroying historic homes and businesses, centers of culture and community life, and even part of a popular water park the city spent millions to build and open in 2014. In response, community groups like Sunshine Citizens worked to stop the project by holding marches, attending public meetings and going to the press.

Their work paid off: In May of 2018, FDOT announced they were cancelling the project due to “community opposition.”

In part because of that decision, the community is thriving. A newspaper column published in the Tampa Bay Times notes that “Tampa Heights is exploding” with bars and restaurants, and with more pedestrians and bicyclists than ever (although not enough crosswalks). Rather than building a bigger highway, the neighborhood has been working to slow traffic. Palm Avenue, which runs across I-275, was put on a “road diet” with more space for pedestrians and bicyclists, and slower speeds. Sunshine Citizens is currently building support for a project to convert the raised I-275 highway into a multi-modal boulevard that supports walking, biking, and light rail.

Unfortunately, Tampa’s story isn’t a typical one. The more common refrain goes something like this. After a 2001 earthquake damaged the Alaskan Way Viaduct, an elevated highway along Seattle’s downtown waterfront, the city began planning a replacement tunnel that would increase total traffic capacity. The tunnel project not only came with an exorbitant price tag, but it was also unlikely to reduce congestion, according to the state’s own data. Nevertheless, Seattle moved forward with the tunnel. After falling more than three years behind schedule and running more than $200 million over budget, the tunnel opened in February 2019.

But before the tunnel opened, the closure of the old Viaduct highway provided a real-time experiment of what happens when a city removes an urban highway. The Viaduct was closed three weeks before the new tunnel was set to open, an event termed “Viadoom” by the local media, with predictions of interminable traffic jams in the period between the closing of the old highway and the opening of the new. But the predicted traffic never materialized.

Instead, with both highways closed, the traffic seemed to melt away. The Seattle Times asked: “What happened to the 90,000 cars a day the viaduct carried before it closed?” There were many possible reasons: More people commuted by bus, bike, and water taxi, with transit riders benefitting from expanded service made possible by a recent boost in local public transportation investment. Others changed their commutes or just worked from home.

The phenomenon was induced travel in reverse: Remove highway capacity, and people find ways to drive less. As Mark Burfeind of INRIX, a traffic analytics company, told the Times: “For lack of a better term, the cars just disappeared.”

Today, the new tunnel is up and running. Many commuters have resumed their old habits, and peak time traffic counts are already slightly higher than they were on the viaduct.

What should cities do?

Sometimes, what we don’t build is more important than what we do build. Cities should rethink any plans to add freeway capacity, and consider reducing capacity instead. As we saw in Seattle, reducing capacity, even without doing anything else differently, doesn’t lead to “carmageddon.” People find other ways to get around.

It only lasted a few weeks in Seattle, because a new $3 billion tunnel opened not long after the old freeway closed. But a number of other cities have decommissioned urban freeways (without opening new ones) and seen positive results: the Harbor Drive in Portland, Oregon, the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco and the Park East Freeway in Milwaukee, to name a few. In all three cases, the cities were able to improve the quality of life for residents while seeing some decreases in traffic.

Portland residents now enjoy a waterfront park at the site of the old Harbor Drive Freeway. Image: LaValle PDX, Flickr.

Better yet, at the same time we are decommissioning freeways, we should be investing in lower impact modes of transportation, including public transit, walking, and biking. Even if there’s still traffic around the city, at least people will have more options to avoid it. And if we’re going to have any chance of meeting short or long term climate or clean air goals, we have to get people out of their cars and onto a bus, bike, or their feet. But that will only happen if we stop building newer and bigger highways and instead focus our efforts on making it easier for people to drive less and live more.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

5 Comments

Submit a Comment

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

Americans should look north occasionally. In Vancouver, in Canada, that country just a few inches away, the initial decision to forego freeways in the 70s has produced a vital redevelopment of the downtown and a rich economy. This is the new way to build cities. As we now understand, retrofits are good but never building the damn things is even better – and the no-freeway outcomes, seen over time, are very relevant to the retrofits.

Freeway expansion does not necessarily cause renewed congestion, and when it does, many more people are traveling (with various modes not just SOVs), which is mostly a good thing. More travel is a symptom of a vibrant economy. When supply increases, and demand stays the same, price goes down and consumption grows (movement along a demand curve). The same situation occurs with preexisting demand and increased road capacity: price of travel declines and that “induces traffic” or consumption of road space. “Induced demand” is not the same thing. I wish commentators and the media would talk to any economist before writing about the erroneous concept of “induced demand.” The fundamental law referred to in the commentary is actually a conclusion in an article that increased road capacity or transit will not reduce congestion. That’s hardly a fundamental law.

Vancouver, Canada, provides another example of the consequences of saying ‘No’ to freeways. In the late 1960’s protests against a proposed freeway into downtown stopped construction. City Councils since 1972 continued the ‘No Freeway’ stance. The feared congestion didn’t happen. Results were quick to materialize. In 1976, 90% of people accessed the Downtown by car. By 1992, car travel was down to 70%. By 2009 drivers had decreased to 58%. Concurrently the Downtown population increased by 75%, jobs increased by 26%, as the number of vehicles entering the downtown dropped by 20%. Today Vancouver’s downtown is a vibrant family friendly center with access by walking, biking, and transit continuing to increase.

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/transportation-2040-plan.pdf

https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/2018-transportation-panel-survey.pdf

Observing the decline in traffic in a zero option condition of a few weeks is not as meaningful as the author wants me to believe. It certainly was not good for business owners dependent on the commuter flow. Staying home doesn’t lead to a better society and electric vehicles charged by nuclear power grid is the global warming solution.

I submit the reason for the singular focus on highway expansion and automobile transportation is the maintenance of a transportation monopoly. The motor vehicle mode is a monopoly that provides a guaranteed market for fossil fuels, car makers, and bank loans. It is also the essential feature of suburban real estate development. This suburban RE + motor vehicle transport is the ideal infrastructure design to maximize profits for the banking cartel. Mortgage loans, car loans, wall street finance, fossil fuel corporations, and the Military Industrial Complex are all designed around this debt and money environment. A key underappreciated fact is that banks actually create new money when they make these loans — hence the importance is greater than it might appear. I have followed this issue for years and I have yet to see one expert go beyond the obvious inefficiencies and incongruities — congestion and pollution. Never mind that the highway transportation system is the most wasteful system imaginable, providing the least per unit of energy, space, or money. Highways and suburbia are promoted by the establishment because of the alignment of banking, manufacturing, fossil fuels, and defense. The money for all this “economic growth” is created in the process, which gives it an impetus that simply is not there for competing modes. Hence, it is more than just realizing highways don’t help cities and making some room for pedestrians, bicycles, and buses.

Since my rant here is a variety of “follow the money,” I am wondering if there any studies that show the circulation of money used for mortgage and car payments. I suspect it is minimal, i.e. straight from the paycheck to wall street. Whereas, in contrast, using bicycles and public transportation, money might circulate in the local area for more turns and a longer time. At any rate, I also suspect the hand wringing over the motor vehicle transportation system will continue until such time as the banking cartel and corporations have collapsed and been swept away by “circumstances beyond our control.”