Resilience Calls for Smart Planning and Great Leadership

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

In the 1940’s, when Houston’s population was about 400,000 following devastating floods of 1935, city leaders constructed two large reservoirs outside the city to act as detention ponds, should another storm threaten their community. In the decades that followed, however, different leaders, more interested in capitalizing on the boom in oil and gas production, encroached upon these reservoirs, even permitting development within the basins themselves. Predictably, in 2017, when Hurricane Harvey blew through Harris County, the reservoirs and the surrounding area filled with water, displacing tens of thousands and causing more than $125 billion in damage and economic loss. The New York Times wrote, “Resettling neighborhoods, making certain places off-limits to development, creating dikes and reservoirs is difficult, both financially and politically. It takes longer than most election cycles. Memories fade. Inertia sets in. Residents just want to get their lives back to normal. Politicians want votes, not trouble.”

Houston, following the floods of 2017

When the Northridge Earthquake struck in the early morning of January, 1994, the City of Santa Monica, about 15 miles south of the epicenter, avoided a direct hit. Nonetheless, many unreinforced masonry, steel, and multi-story wood framed buildings were damaged. Aware that it was only a matter of time before one of the faults under or nearer the city ruptured, possibly leading to massive damage and both social and economic disruption, city leaders passed regulations requiring the mandatory retrofit of the community’s most vulnerable building types. This culminated in a 2017 ordinance that is considered one of the most extensive in the country. Mayor Ted Winterer, in explaining the city’s decision, said “We want to do as much as we can to limit the loss of life and infrastructure, so in the event of a disaster, we bounce back strong.”

Vulnerable buildings, in the City of Santa Monica

Resilience is a measure of how quickly a system recovers – bounces back – from adverse events. These can be chronic stresses or acute shocks. The former are ongoing demands on a community, a company, even a family, that require the constant attention of leadership. Homelessness, economic competitiveness and crime are all examples of chronic stresses. They are ever present to some extent and leaders measure their success in addressing these stresses by the near term results their policies achieve.

Acute shocks are events that occur infrequently, like natural disasters. They are rare, but their impacts can be devastating, as we saw with the floods in Houston. The challenge for leadership is that policies that they may enact now to make their communities or businesses more resilient may not bear fruit during their tenure – on the city council, in state legislature, or on the board of directors for example. And mitigating these risks now may take away resources that could be put toward addressing the chronic stresses.

Ordinary, even good leaders, often focus on addressing chronic stresses because the return is typically more immediate and the benefits accrue to them. Great leaders, however, know that their lasting legacy will be in part measured by how they thought about the long-term, and the economic and social security of generations that come after them. Traits of great leaders are the traits we see in heroes: they make decisions not for themselves, but for others.

The examples of Houston and Santa Monica, or the example of the Houston of the 1940’s and the Houston of today, are tales of two cities, tales of ordinary versus great leadership.

Fear + Hope, and a Plan

An objective of the US Resiliency Council is to help ordinary leaders become great leaders, using the strategy “Fear plus Hope and a Plan.” “Fear” is just a recognition that for acute stresses like earthquakes, hurricanes or flood, leaders must adopt a when, not if, mentality. An “if” mentality really means, “will the event happen on my watch? While I’m mayor, governor, or CEO, or while I own this home?” Someone with an if mentality is willing to roll the dice and risk that the event won’t occur until they are long gone. But that mentality is also one that does not consider the value of future generations as much as their own.

Bioethicists coined the term “circle of empathy” to define the size of the group with which an individual can feel compassion or responsibility. The more evolved the species, the larger that circle becomes. The evolution of ordinary leaders into great leaders requires a temporal expansion of that circle, to include members of their community not only today, but in the years and decades that follow. This is how we define a when mentality. Regarding acute shocks, great leaders understand that “when” the even happens, even “if” it does not happen on their watch, it will still affect hundreds or thousands of people. And to great leaders, reducing the impact on future generations is just as important to them as protecting their own constituents.

Fear can spurn action but it can often be paralyzing. When it comes to “acts of God,” leaders can take a fatalistic or resigned approach. We can’t prevent earthquakes or hurricanes, so if the big one hits, what really can we do about it? The fallacy in this approach is an all or nothing perspective. The belief that if I cannot solve the entire problem, then why bother?

There are few things that politicians like more than cutting ribbons – to open the new shopping center or bridge, to be there at both a project’s groundbreaking and its completion. I think of the building of ancient cathedrals in Europe that often took a hundred years or more. The duke or bishop that started the project was never able to cut the ribbon when the last stone was placed. Realistically, their children or even grandchildren may not have seen that day. But these leaders saw a bigger goal in what they were doing, and their legacy was cemented in the vision they had, not the photo op at the end. You might ask two different masons working on that church’s foundation what they were doing. One would say that he was just laying bricks. The other would proclaim, “I am doing God’s work.” The first sees only his job, and the rewards he receives each time he collects his paycheck. The second knows that what he does each day is contributing to a larger, more beautiful and nobler goal, and it is the participation alone in that beauty that is the reward.

Hope, the second element of the USRC’s strategy, encourages leaders that it is meaningful to move the ball forward, and contribute a share of the solution. When it comes to resilience to natural disasters, the problem is so large that it will never be solved by one person. But that is not a reason not to lay the foundation or take the baton midway through the race and advance the goal in a measurable way.

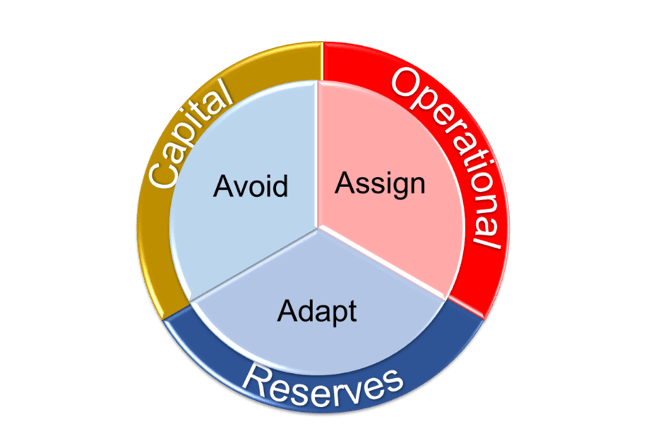

Resilience Strategies – Avoid, Assign, Adapt

The hard work of becoming a more resilient community, company, or family has to start with a plan. Even with the best of intentions it can be hard to know where to begin, or how to balance the resources available with the impacts they will have. The good news, when it comes to resilience, however, is that leaders can employ a range of strategies that together will achieve great things. The USRC calls these: Avoid, Assign and Adapt.

Avoidance is the most effective way to combat disasters by reducing their impacts. It is not usually possible to avoid the hazard itself. Santa Monica can no more pick up and move itself out of an earthquake zone than Houston can stop another hurricane from crashing into the city. But implementing seismic retrofit ordinances, designing buildings to higher performance standards, or building flood control infrastructure like reservoirs or levees, can lessen the effect of the hit, when it comes. The National Institute of Building Sciences estimates that for every dollar spent on mitigation, four to seven dollars are saved in reduced damage and economic impacts.Avoidance can be capital intensive, so it is not typically the only way leaders reduce risk.

Assignment is the sharing of risk, either through financial mechanisms like insurance, or through mutual aid agreements between entities. To combat the wildfires currently ravaging California, the state fire service has brought in support from as far away as Australia. We buy fire insurance for our home and pay a small premium each year, which most of the time goes to cover other people’s claims, in the expectation that if a fire destroys our house, payments from others will be made to us. Sharing risk and resources spreads out costs in a way that can fit into annual operating budgets.Even with best laid plans, when disaster strikes there will still be impacts.

Adaptation recognizes that preparedness and response will always be essential requirements of recovery. Examples of adaptation are education, training, developing continuity of operations plans, and putting aside funds into an emergency reserve. These tactics are relatively low cost but can make the difference between recovery that takes weeks or months versus years.

The mission of the USRC is to encourage great leadership, whether you lead a city, a company or your family. Ordinary leaders become great leaders by thinking about the long term – a when not if mentality – believing that it is as just as important to contribute to a solution as it is to be the one to cut the ribbon, and knowing that their legacy will not be measured only by the short term successes they achieve, but by the positive impacts they have on generations to come.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

Thank you for the content of the article is stimulating towards me and I hope that it is not the only one in my community that starts this way, I have two years two months of wanting to implement a process of resilience in the hydrological water cycle, to provide this vital liquid to a community of 46 marginal neighborhoods, but the struggle is hard, but I do not decay, so thank you very much for these very comfortable letters, that I am not alone in my initiative. I already managed to unite the private company, the academy, the civil society, but the government is hard to understand.

Nice article. A fresh way of looking at a long-persisting problem.