Multi-modal Transit and the Public Realm

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

How emerging mobility technologies can support multi-modal public transit in a post-pandemic future.

Cities have been severely impacted by COVID-19 on a number of fronts, and it has laid bare the severe disparities that result from ever-dwindling budgets. The pandemic has also dramatically changed how we experience the urban environment and required us to re-envision how people navigate and interact with their locales.

On a regional basis, commutes to central business districts have dropped dramatically, while surrounding town centers, however small they may be, have gained more activity. For the privileged, who have the ability to shelter-in-place and are supported by flexible work-from-home policies, trips have become more concentrated near their homes and rarely reach beyond neighborhood amenities. As a result, open-street networks have blossomed to allow more space for walking and biking, and cities have pivoted to allow restaurants to expand outdoor dining and retail areas into the public right-of-way (ROW). A map released by Lime, a scooter-share company, showed that, over the summer of 2020, trips have become more concentrated within neighborhoods, rather than sprawling across the city. Meanwhile, Apple Mobility Data showed that private driving returned to pre-COVID levels, after a brief reprieve in April 2020, while transit ridership is still well below normal.

It is clear that this crisis has impacted communities in very different ways. While central business district commutes might have fallen during the pandemic, cross-town trips persisted, and these are more representative of essential workers’ routes. Cities have adjusted their transit systems, cutting some routes in order to ensure more resources for higher volume routes, or contracting out late night or expanded service areas in order to ensure that all customers can be continuously served.

These changes in transportation patterns should inform how we analyze and address old problems. A longstanding challenge has been how to meet the growing transportation demand across an entire region and during traditionally off-peak times, while also ensuring that neighborhoods, town centers, and other nodes outside of the central business district can be supported with sustainable mobility options. Historically, and more than ever today, the most convenient way to travel within a region is by private car. But, as we look forward to a post-pandemic public realm, could emerging mobility technologies help?

More than ever, urban transit services are in need of sustainable and affordable solutions to better serve all members of our diverse communities, not least among them, those that are traditionally car-dependent. New mobility technologies can be a potential resource for local transit agencies to augment multi-modal connectivity across existing transit infrastructures. As we all witnessed in the last decade, technological innovation (like transportation network companies and micro-mobility) has triggered a profound transformation of the urban mobility ecosystem, enabling new shared, on-demand, and multi-modal transportation options. By being open to new technologies in the realms of both operations and vehicles, transit agencies can establish a more resilient and sustainable urban mobility ecosystem and even remove some of the friction in payment and trip-planning.

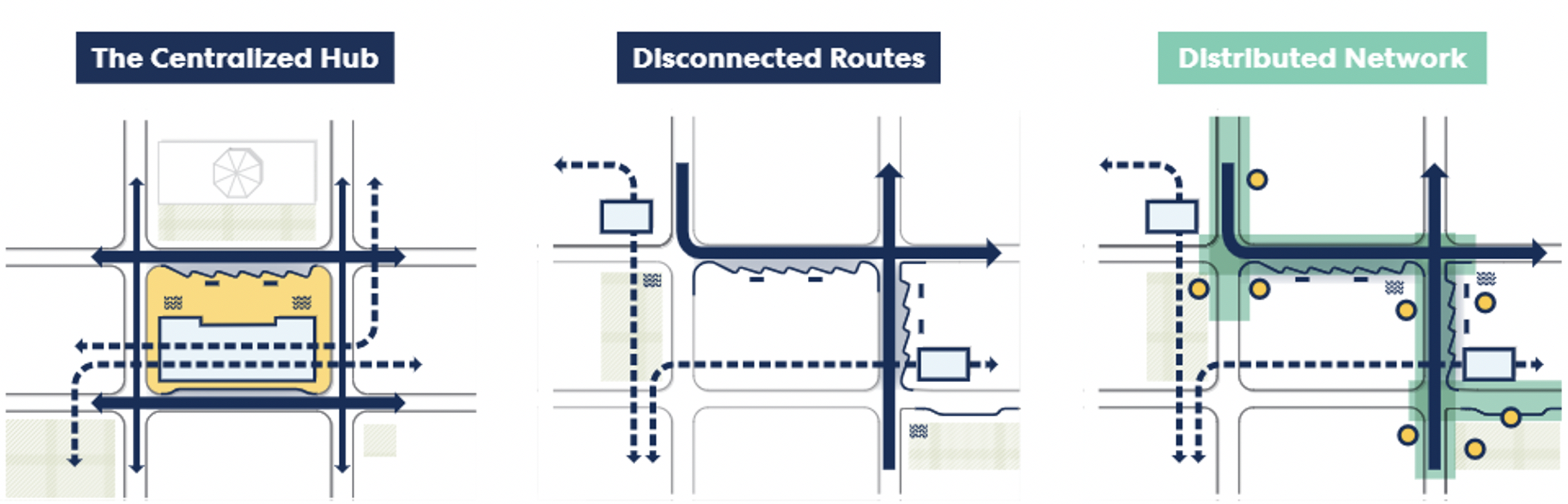

We envision a new decentralized and distributed model that provides multi-modal access through nimble and flexible multi-modal Transit Districts, rather than through traditional, centralized, and often too expensive Multi-modal Transit Hubs.

Working in collaboration with existing agencies, new micro-mobility technologies could provide greater and seamless access to existing transit infrastructure, while maximizing the potential of the public realm, creating an experience that many could enjoy beyond just catching the next bus or finding a scooter. So how would we go about it?

- Step 1: Identify an area of the city with the highest concentration of transit services (e.g., local bus stops, light rail, etc.). For many communities, multi-modal transit services, when provided, come in the form of uncoordinated schedules, infrequent service, and physically disjointed and often unsafe stops located across multiple city blocks. While such areas are served by a certain level of multi-modal transit, the physical conditions in these public realms make the user experience unappealing for most, which results in low transit ridership, a deserted public realm, and an increase car traffic (along with attendant pollution).

- Step 2: Define the most convenient path to access each transit mode available within walking or biking distance. What are the most trafficked and convenient routes to get from one mode to another for a local transit rider? Can we determine an area within walking or biking distance that includes the most comprehensive range of local transit options available? And are there specific landmarks, destinations, and ground floor activities that could enhance these commutes?

- Step 3: Provide the glue. Provide micro-mobility services and enhanced public realm solutions that enable easier, more convenient, and more desirable access to local transit. Imagine an open-air concourse: an area of the city geared to best serve pedestrians and transit commuters alike, where wider sidewalks clearly and intuitively lead you from one transit mode to another; where shared bicycle and e-scooter services are readily accessible near each local transit stop and have safe and dedicated lanes. This would be an area of the city with existing landmark destinations, active ground floors, and tailored wayfinding strategies are all coordinated to support a convenient and attractive mode transfer; where each single strategy that best serves the commuter also has positive outcomes for local residents and businesses by way of providing a more vibrant, pedestrian-oriented, and safe public realm.

The measures listed above range from low-cost, temporary solutions to permanent, long-term investments, and this range is key to a step-by-step implementation approach that should benefit communities with limited financial resources. To start, temporary parklets, paired with shared bike and e-scooter docking stations, could be located next to key local transit stops, serving commuters and providing opportunities to engage with existing ground-floor businesses. An easily identifiable network of paths comprised of easy to deploy low-tech way-finding solutions and dedicated micro-mobility lanes could allow commuters to intuitively find their way to the next stop.

Tactical urbanism strategies, many of which we have seen deployed in cities as a response to the current health crisis, have demonstrated how big changes can happen with small budgets when there is the will and the support of local communities. In the long term, access to efficient multi-modal services and the resulting vibrant public realm could represent a catalyst for new urban development infill to support long term capital investments.

Phasing diagrams

As the network expands beyond the central district, there are opportunities to meet demand more easily, particularly through the use of on-demand, shared transportation that is integrated with fixed route transit. Beyond the initial identification of one area that has a concentration of transit and micro-mobility, there may be several nodes throughout a region that have been reinvigorated post-COVID, and thus could benefit from the distributed transit network model as well. This coincides with shifts away from traditional “hub-and-spoke” transit models and towards an approach that allows greater lateral movement outside the city center. Imagine regions that are no longer concentrated around a single anchor of the central business district, but that have multiple anchor districts that connect to one another. And within those nodes, many points of connection could allow people to move around freely along an enhanced public realm.

Crises expose and deepen underlying societal inequity. Urban residents are now more than ever relying on the public realm to access jobs and services, conduct a healthy lifestyle, and nurture social relations. The current crisis is causing us to reconsider both the nature of transit and the role of the public realm. As a fundamental public service, public transit should be conceived as a scalable, resilient, and adaptive system, that helps communities where they are, from large cities to small towns; a system that relies on affordable and easy to deploy solutions that is at the foundation of more equitable and thriving urban communities.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

We need to define and differentiate terms. Transit Hubs are Envisioned to link fixed route shuttle and demand response feeder services in suburban areas. The concepts addressed in this pace are for urban central transit linkages. The former requires safe efficient and monitored venues hopefully by a convenience store or other business activity that has late night service to enable safe transferring between modes. The linkages discussed in this article are urban or a small town useful on the pulse system where you don’t want to allocate a separate space to sequester transit riders but rather how the transferring occur in the business district were so maybe choose to grab a cuppa coffee coffee or a doughnut or something on the way to the other bus the reliance on micro mobility concerns me as a 65-year-old was not going to get on a scooter linkages need to be fully accessible to all riders including those with disabilities, strollers and luggage.