From Local to Global: Food Security for Urban Centers

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

This past July, I was in a Top’s Market in Chaing Rai, Thailand, purchasing groceries for the week, when I came across Driscroll’s organic strawberries from California. Staring at the all-too-familiar packaging from my usual grocer in San Francisco, I experienced a mixed sensation of befuddlement and dread.

A similar sensation came when I recently read about rooftop organic gardens in Hong Kong importing organic soil from Germany. According to the New York Times’ article, City Farms, the Hong Kong rooftop gardening operation, had to adjust the soil for Hong Kong’s humid climate. The idea of transporting organic soil 5,600 miles to create organic rooftop gardens – an undertaking promoting local food production – seems intrinsically confused.

Photo Credit: Blogger Saucy Onion

In the sustainability world, we hear a lot about the benefits of eating locally, urban agriculture, and creating local food sheds. Concurrent to the local food movement, there are powerful global trends occurring in food as well – the transport of organic food and soil across the world being just one of them. The key parallel between the local movement and the global movement is the attempt to secure a food supply for a growing population.

The Global Land Grab

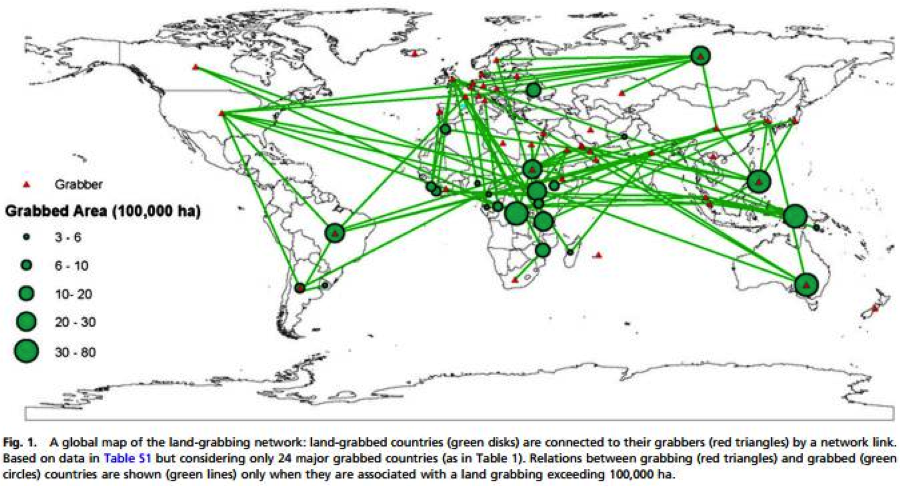

China, the US, the UK, and the United Arab Emirates are currently the largest purchasers of foreign land in what is being called Land Grabbing, or purchasing land in other countries for agricultural use. Land Grabbing began as a response to 2007-2008 spikes in food prices. The purpose of Land Grabbing is to secure food sources for growing populations, guarantee a water supply for agriculture, and diversify a country’s source of food.

A study released by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) shows that an area of land the size of Germany and France combined have been purchased by foreign investors. As of November 2012, 17% of the Philippines and 19% of Uruguay have been grabbed. The graph below shows the flows of documented land grabbing.

In response to this large-scale exchange of land rights, organizations such as the World Bank are pushing for regulation and transparency in land deals. Other organizations, like the International Peasant’s Movement, La Via Campesina, are calling for the stopping and reversing of land grabbing.

At its core, land grabbing is portrayed as a desire to own the means of food production, a sentiment shared by food activist and rooftop gardener Pui Kwan in Hong Kong, “That’s the whole idea behind it…food security and food safety,” she says in a discussion with a Hong Kong Blogger, “…the only person responsible for your wellbeing is you…why not grow your own food?”

Localized Urban Agriculture

On the opposite end of the spectrum of land grabbing is the idea of localizing and democratizing agriculture through urban farming. As the percentage of urban poor increases (25% in 1988 to 50% in 2000, according to the World Bank) and food prices rise, urban agriculture is a way to secure a food supply for the urban poor. While small-scale operations may not appear to make much of a dent in the localization of food, surprisingly large percentages are being produced in urban areas worldwide. The RUAF Foundation provides the following data:

- In Hanoi, Vietnam, 80% of fresh vegetables are being produced in urban and peri-urban areas

- 90% of Accra, Ghana’s fresh vegetables are produced in the city

- Urban gardens in Havana produce 25,000 tons of food annually

In the United States, the urban agriculture movement has taken root, addressing issues of food deserts and poor nutrition. I recently had the opportunity to volunteer at one of Phat Beets urban gardens in Oakland, CA, pulling weeds out of their raspberry bushes and laying down mulch. Phat Beets has an incredible partnership with the Children’s Hospital of Oakland, allowing doctors to prescribe fresh, locally grown fruits and vegetables to children with diet-related problems.

Phat Beets sells their produce from this and other urban gardens in Northern Oakland at farmers markets and through CSA boxes. Phat Beets and many other urban agricultural organizations are working on a local level to solve issues of food security in urban areas.

As urban density continues to increase (the UN estimates 80% of the population will live in urban areas by 2050), countries, communities, and individuals are looking for ways to solve the issue of food security. What that solution looks like, whether it be grabbing up fertile land in other countries, or growing rooftop gardens, is ours to determine.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

0 Comments