Heritage neighborhoods: what is the value of a tree-lined boulevard?

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

This blog post accompanied a webinar, Creative Repurposing — Unlocking the Past for Our Sustainable Future. Click the link for an archive recording of the event.

Leafy, tree-lined streets with rows of houses dating back a century may be pleasant for a stroll or a springtime run.

But in a world where practical economics rule, do these neighborhoods generate enough value to “pay their own way”? Should these low-density, centrally-located areas yield to what might be perceived to be more efficient use of the land, perhaps high-rise residential developments?

Answering the question requires building a full understanding of what heritage neighborhoods have to offer.

A lighter environmental footprint

Much of the environmental value of heritage neighborhoods is due to the fact that using existing buildings means that additional resources do not have to be consumed for new construction.

However, these neighborhoods have environmental benefits that go well beyond that. Consider:

- Designed before the age of cars, these are walkable neighborhoods – with easy access to parks, schools and retail.

- These are relatively dense developments compared with much of current suburban design.

- Vertical, multi-story construction reduces geographic impact.

- Mature trees provide cooling shade in summer, soak up carbon in the atmosphere and reduce the heat island effect.

These advantages help improve the environmental performance of the city as a whole. Walkability, for example, has health benefits and also reduces the amount of driving, for improved air quality that helps all residents.

An economic “power generator”

One of the values of old, picturesque streets lined with trees is that they are so enjoyable to walk along. This is value that can be tapped.

For example, tourists and other visitors who come to wander through Toronto’s 19th-century Annex might also want to take a stroll into nearby Yorkville, which has some of the most productive retail space in Canada — and itself made up largely of repurposed heritage houses.

Heritage neighborhoods can also generate above-average tax revenue. Solidly-built older homes in established areas are popular real estate. Their residents often upgrade their properties through renovations and other improvements that increase the value of the properties — and the associated tax rates.

Learning from the past

Some of the biggest benefits of heritage neighborhoods come in their value as a technological resource, showcasing building techniques that will become more valuable as time goes on.

Most of the housing stock from the 1800s and early 1900s was designed for a resource-constrained environment — heating with coal and wood was costly and labor-intensive, so houses were designed to take advantage of natural heat and cooling. In our carbon-constrained present and future, the techniques used by builders of yesteryear may see increasing application. For example:

- Houses were oriented, where possible, to face the sun to achieve maximum light through the windows — today called “daylighting”.

- Deciduous trees were planted on the south side of a house, to provide cooling shade in the summer, and their bare branches allowed the sun through to provide heat and light in winter.

- Vines were planted on the south side of buildings, again to provide cooling shade against the summer sun.

- Awnings were angled so that the low-angle winter sun would enter to provide warmth, but inhabitants would be shaded from the heat of the sun — at a higher angle — in summer.

For more information on siting buildings and vegetation around sun and wind factors, see “Siting a building for human comfort” in Sustainable Architecture & Building Magazine, Nov./Dec. 2011.

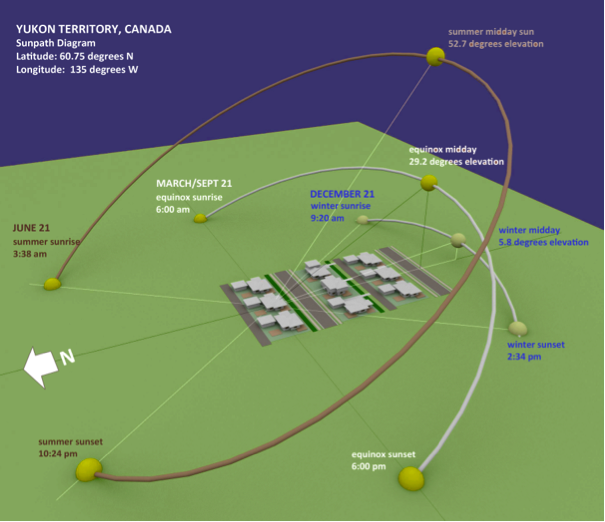

This “sunpath” diagram shows how the sun appears to travel relative to a housing development in the Yukon Territory, demonstrating the value of orienting buildings so they absorb maximum sunlight when it is available. Image by Don Crockett

Applying to the present

Some of the lessons learned from the past can be applied to current developments. For example, studies have shown that mature trees help reduce crime. How? A pleasant, shaded environment draws more people out of their houses, to sit on their front lawns, to walk, and to do yard-work. Neighbors get to know each other better.

This increases the level of informal community “surveillance” — eyes on the street — and as a result, people feel more secure. Children feel safer playing out of doors, and parents feel safe enough to allow them to play. More public surveillance can help reduce the rate of burglaries and other crimes.

Many of these lessons learned from heritage neighborhoods can be modified and applied in conventional greenfield suburban developments, infill brownfield projects and other situations.

Legislative and regulatory environment must be supportive

While tree-lined streets might seem a nice idea, what’s in the way? In some cases, it’s an economic issue.

To keep costs to a minimum, there may be resistance to the idea of devoting land to include boulevards between sidewalk and street. If zoning and other regulations do require boulevards, it may be then be that only a few centimetres of topsoil is put down — enough to support grass, but not to allow trees to flourish to mature stages. Could legislation assist here? Perhaps legislation requiring enough topsoil to support trees would level the playing field – so to speak.

It may be possible to learn from other parts of the world. Many European streets are lined with trees, even without much soil being available — learning best practices might include consultation with municipal planners and getting involved in organizations with wide geographic reach, to learn from best practice elsewhere.

Municipalities may be able to orient new developments so that houses can be situated in a way that takes advantage of sunshine’s benefits, while avoiding its downsides.

While manicured public spaces and lawns might have been considered appropriate in years gone by, we need to re-think this in an age when such features increasingly come at an unacceptable environmental and economic cost.

Featured image by Carl Friesen.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

0 Comments