Behavior Change Case Study: City Systems & Affordable Housing

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

In East Palo Alto, California, a multi-faceted, coalition-driven movement is afoot to assure wider access to affordable housing. This effort, informed by behavioral economics, is helping local homeowners understand and navigate the municipal permitting process for building a new accessory dwelling unit on their property. At the same time, this coalition, of which the nonprofit City Systems is a part, is working to streamline the process of legalizing informal conversion projects already completed without permit approvals in place.

City Systems co-founder Derek Ouyang is a lecturer at Stanford University in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering’s Sustainable Urban Systems (SUS) graduate program, where project-based learning enables students to work directly with local stakeholders in the “messy weeds” on real-life social issues. A Stanford graduate himself, Derek says “SUS differentiates itself from typical engineering programs by taking a multidisciplinary approach to instruction, bringing in politics, ethical reasoning, and the broader set of skills necessary to understand and apply models and interventions.”

SUS has created meaningful relationships with local communities—city and county government, and nonprofits—over the years, “but it was challenging to have students engage in and finish meaningful projects in the community due to the academic calendar.” Frustrated by this cyclical challenge, in 2017 Derek launched the nonprofit City Systems, which takes on similar kinds of projects as SUS, and approaches the work in similar ways.

A majority of this work involves ensuring wider affordable housing access in San Mateo County. A particular focal point is the City of East Palo Alto, “where a high concentration of people who are low-income and/or foreign-born face housing shortage, overcrowding, and instability,” explains Derek. Here, with seemingly few options for recourse, many homeowners have built informal—that is, unpermitted—accessory dwelling units on their property.

Many renters live in these illegally-built units, which may be as simple as a partially-converted garage, because they have no other choice. “We see this informality as a direct outcome of the formal municipal process not enabling sufficient housing in the area,” says Derek. “Because there are legitimate concerns about whether or not these units are safe and habitable, we wanted to see if we could do something about it.”

“It finally became a code enforcement issue. We aren’t sure what caused it, but in early 2016, there were suddenly over sixty ‘red tags’ on homeowner doors all over the community,” explains Derek. The red tag is an enforcement action that involves legal pressure on the homeowner. “They have thirty days from receipt of that red tag to resolve the issue, or else face eviction of that informal unit,” Derek explains. “There’s been a pervasive sense of hopelessness and frustration in the community about it.”

“As you might imagine, it has led to a lot of conflict. The city is cracking down on a valid safety concern, while at the same time, families feel they have no choice. Many are doing this [informal garage conversions] as a means to sustain their livelihood.” This is the political tension—between community members and their city—in which City Systems has sought solutions.

“We started wondering what might be done from a policy perspective. What can be learned from the process of getting a garage conversion or home addition properly permitted? How could we use what we learn to help other homeowners navigate that process?” Derek and his team secured philanthropic funding to work on, resolve, and learn from four of these sixty-plus “red tag” projects.

“These first four will definitely provide a direct benefit to those four homeowner families. But they will also help our team gain tremendous insight into how we can streamline the process the other homeowners need to navigate to resolve their red tags,” Derek says. Toward that end, City Systems was invited to join a partnership coalition with a handful of organizations that each contribute to this undertaking, including:

- Rebuilding Together Peninsula – a general contractor akin to a Habitat for Humanity that initiated formation of the coalition

- SOUP – a nonprofit developer of accessory dwelling units

- EPACANDO – a community development corporation working to build a loan product

- Faith in Action – a network of congregations and a community voice at the table

“We’ve been working together for a couple years now,” says Derek. “We have monthly meetings between us, and the city planner, and code enforcement, and we’ve forged a productive working relationship. We decided together to take on the barriers that many people are encountering,” which Derek describes as:

- Process barriers

- Trust barriers

- Policy barriers

Process Barriers

Derek says there were numerous questions his team identified at the outset of the project. “What can I do? What are the steps I need to take? What are my rights? It’s a highly bureaucratic process. There’s a lot of paperwork, a lot of legal requirements. How can I gain the knowledge I need to complete and submit my package of paperwork and renovation plans properly the first time?”

Derek says once an applicant submits their paperwork, the city has thirty days to process it and respond. “They generally take the full thirty days because the system is so backlogged,” Derek explains. “And when you re-submit after addressing an error or omission, there’s another thirty-day review window. This isn’t necessarily an intentional delay, but it’s the way it is. This slow, unpredictable process makes many projects infeasible. Waiting more than sixty days may well mean a family faces displacement and the disruption of life that can come in the aftermath.”

From an architect’s perspective, Derek says, he and his team have learned a lot from working on the first four “red tag” projects. “We have a much better sense of what needs to be done now. Seventy-five percent of the paperwork involves standard building code requirements common to all construction projects. Little of what is needed is unique to any given project.”

With this information and insight, Derek says “we developed a template form after we completed the paperwork for our first four red tag projects. The only details a homeowner has to add are those unique to your property—the shape of your house, and a few other simple calculations,” says Derek. “Now anyone can go online and download mostly complete drawings. You’ll only have to add a few key pieces of information, so it’ll be vastly easier.”

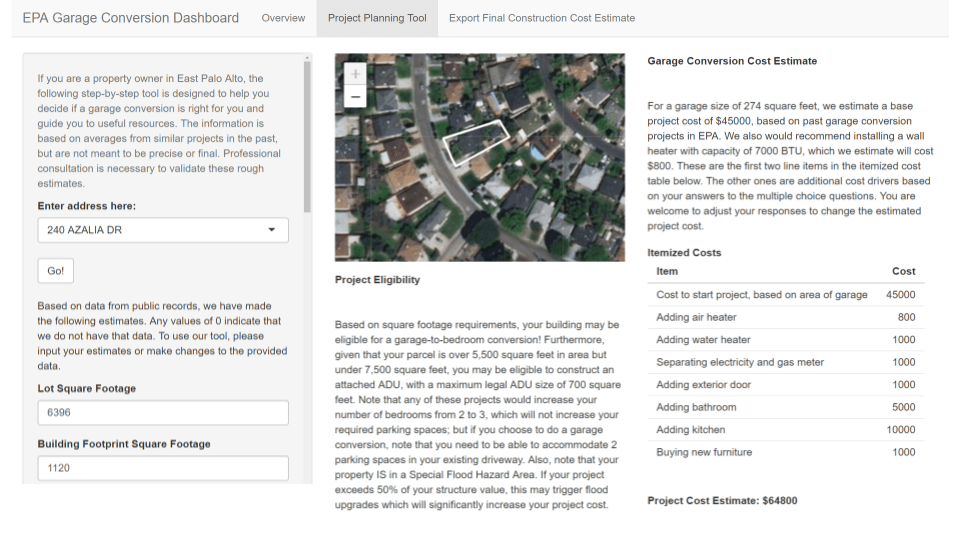

Derek explains: “One of the key inputs you need is the official record of your property’s size, its cash value, the number of beds and bathrooms, that sort of thing. Normally the homeowner must go to the County to get this information, but to eliminate that barrier, we developed a web tool so a homeowner just has to type in on their address, zoom in on their property, and find the information they need. The tool also generates an estimate for how much the project would cost.”

If a homeowner’s renovation has been done without permitting, the site will also flag the cost drivers related to bringing it into compliance. “When the homeowner arrives at the end of that web tool, they can click ‘print’ and take it to a meeting with the city planner or an architect,” Derek explains. “We’re trying to create access to useful information—the digital version of a homeowner’s do-it-yourself guide through the process.”

Trust Barriers

Another barrier in the process of legitimizing informal renovations after the fact is the general lack of trust that community members have in the City of East Palo Alto. The city government, only formally incorporated in the late 1980s, is sorely understaffed and under-resourced. Because it’s a relatively new municipality, it missed out on shaping important regional policy issues, including resource allocations like water rights and tax revenues. “This put East Palo Alto at a regional disadvantage, a positioning from which it hasn’t yet recovered,” says Derek.

At the same time, the high concentration of foreign-born people, particularly those coming from island nations, means “there’s less experience or understanding of U.S. municipal systems. Many people don’t realize there’s such a thing as governmental oversight and permitting of home renovations. Residents have been scared and frustrated—they want to do the right thing, but they don’t know where to begin, and they don’t feel comfortable talking with city officials for fear of fines, eviction, or worse, the threat of deportation,” Derek explains.

City Systems being a nonprofit third-party intermediary has been critical in breaking down the trust barrier. “Folks who have already done a home renovation informally need to be able to speak candidly with someone about their situation, so they can figure out what options they have,” Derek says. “It’s been uplifting to see that this process does work. City Systems and our partners have been creating important communication channels, and cultivating a sense of trust through intermediary dialogue. The local government recognizes the value of our role, and has been very supportive of what we’re doing.”

To get the word out has taken very intentional work on City Systems’ part. “We’ve been doing a lot of these outreach events. We know people are in need of resources, and information about how to access them. We started with two small-scale community meetings, but only about ten households attended each,” Derek says. “We knew the magnitude of the problem was so much bigger than that, and quickly realized we had an outreach problem.”

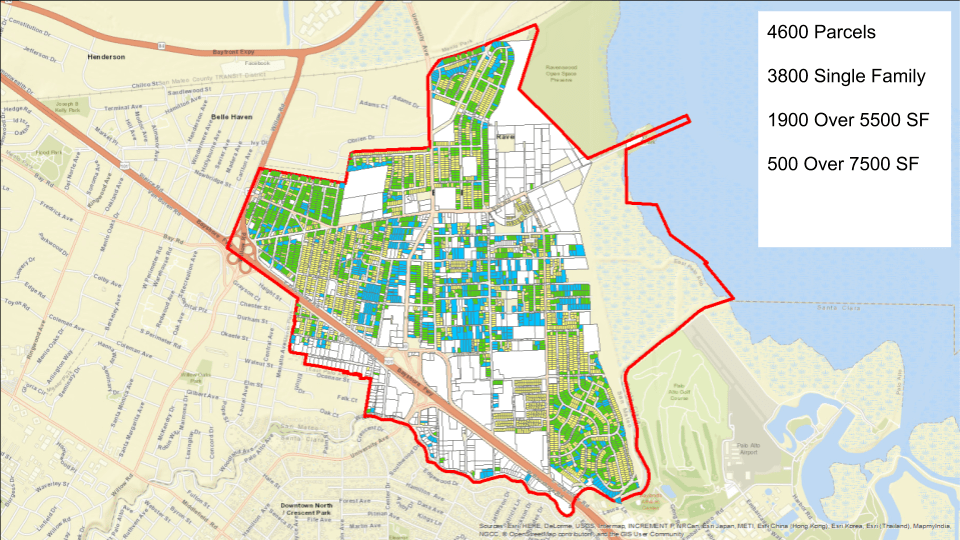

So, his team took the outreach work a step further. “Because we have macro-scale data about the city, we predetermined who was eligible to create what kind of accessory unit on their property based on lot size and zoning. We created a custom postcard mailer that we sent out to over four thousand households in the weeks prior to our outreach event. We held the event in a church parking lot on a Saturday, and because of that mailing, we had over seventy households show up and sign in,” he explains.

“At that same event, we brought a model modular unit so folks could see what their ideal renovation or upgrade could look like. We did fifteen-minute mini homeowner consultations. We walked folks through the web tool, step by step, and upon seeing their options, were able to brainstorm ideas together. This last time, we had dozens of people waiting in line for consultations, so we knew we’d finally gotten the outreach right,” Derek says.

Policy Barriers

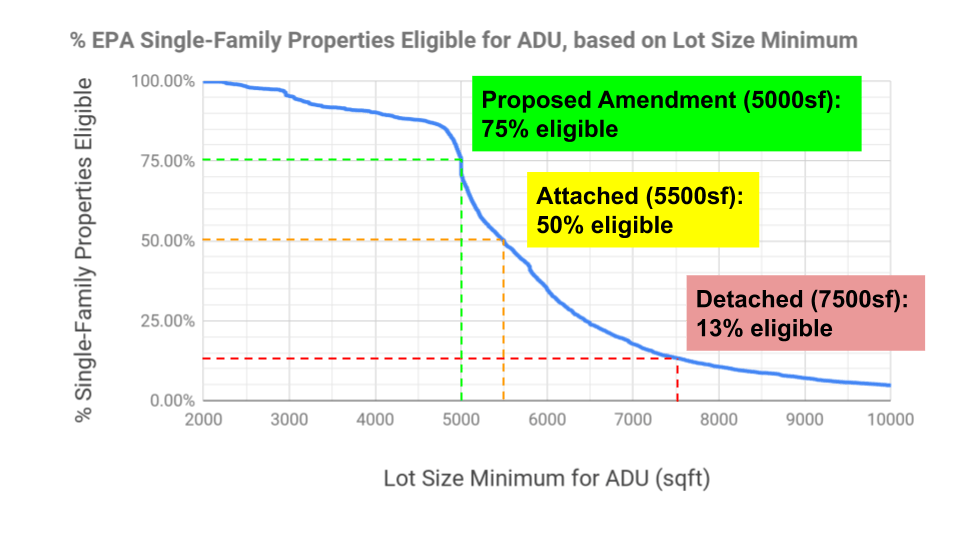

“As much opportunity as there might seem to be for making renovations to your own property, there are layers of exclusion built into the zoning code that limit what many homeowners can actually do in East Palo Alto,” says Derek. “When we started looking at what homeowners could do by right, our operating assumption was that a whole new stand-alone unit in the backyard would make for the best living conditions while increasing housing availability. But, by the books in East Palo Alto, such an upgrade requires that the size of the lot be 7,500 square feet.”

“If you look citywide at eligibility for building this kind of accessory dwelling unit, only about twelve to fifteen percent of lots qualify. If the city were to modify the policy by reducing the eligible lot size to 5,000 square feet, all of a sudden 75 percent of the parcels citywide would qualify,” explains Derek. “Our team created GIS maps and charts showing the potential impact that this small policy shift would have on the community. It’s a powerful visual. We hope that re-framing the problem as something city planners can solve, and communicating these issues alongside homeowners, can create a behavioral nudge in the right direction.”

Derek remains hopeful that investing time and energy in the coalition will help. “We’ve built bridges. We’ve been working tirelessly with City Hall for a while now. Hopefully I can leverage these relationships as I eventually make the case to City Council in a rational way for reducing these lot size requirements. I’ll add in anecdotes from the conversations we’ve been having with real-life homeowners to help change their minds,” he says.

There are biases that need to be checked within the regional discourse, too. “At the county level, there have been some efforts to get more homeowners to understand their options. The problem has been that most of San Mateo County’s population is wealthier, whiter, and older than East Palo Alto’s. The county’s default numbers and messaging were attuned to a demographic that was decidedly not East Palo Alto, where sixty percent of the population is Spanish speaking, compared with just twenty percent county-wide,” Derek explains. “What’s more, the informal, unpermitted renovations are numerous in East Palo Alto, and none of the county’s communications assumed that as a starting point. So, it clarified the need for our work—we needed to re-frame the messaging and the focus to make it relevant and salient to the East Palo Alto audience.”

This work raises a much larger question for Derek and his team as they look ahead. “Our web tool is dedicated to unlocking awareness at the individual and household level. But we’re also looking to build awareness, and advance change, at the systems or community-wide level. And with those aspirations comes the question: at what level is it most effective to communicate? Are we better served aiming to connect with the individual, or more broadly across the whole community?” This sensibility guides Derek and the City Systems team as they scan the horizon for other projects to take on, too.

Supporting climate adaptation and resilience planning in East Palo Alto is a burgeoning area of focus for the organization. “We’re asking these same questions with the climate change work we’ve been scoping. We know that about half the parcels in East Palo Alto are at great risk for flooding and sea level rise impacts. At the same time, there are tons of parcels inland and uphill whose owners aren’t at risk at all,” Derek says. “The information we communicate will land much differently with the most vulnerable residents than it will with those who won’t face the most intense impacts.”

“We need to find a way to strike a balance in our communications. We need to develop messaging that helps us all feel a sense of empathy for one another. We need to cultivate a ‘we’re all in this together’ response in place of ‘I’ve got mine’. We haven’t figured this out yet, but it’s definitely an important thing we’ve got to do, and hopefully this affordable housing work will help us better understand how to do it justice.”

Behavior Change Analysis

The work that City Systems and its partners is leading to increase the supply of affordable housing in East Palo Alto offers important lessons about the use of behavioral economics at the individual, group, and community-wide levels.

The slow, inefficient permit application review process demonstrates the strong potential impact that a set of INCENTIVES could have on affordable housing supply in the Bay Area, and especially East Palo Alto. For city planners, incentives could help increase the speed of staff review and processing of paperwork. For homeowners, an incentive might make them more likely to enter the process at all, so long as they’re assured their efforts would be met with an efficient response and proactive, collaborative problem-solving.

Derek’s team creating a web tool template for homeowners to use in developing and submitting plans and permit applications demonstrates how City Systems is making it EASY for homeowners to be proactive in following the law and participating in a convenient, predictable municipal process.

City Systems’ role as a third-party intermediary between homeowners and local government speaks to the power held by a good MESSENGER for shifting behaviors. By establishing trusted relationships and holding safe space with and for homeowners to explore their options without fear of getting in trouble, the nonprofit is gathering and conveying important information from and between both the municipality and homeowner, thereby bridging an essential gap.

Derek and his team taking time to pre-determine homeowners’ by-right options for building an accessory dwelling unit on their property is a marketing effort that makes important information RELEVANT and SALIENT to those homeowners. In the near-term, this approach helped turn people out to City Systems’ informational session and contributed to the knowledge base in the community. In the long run, this effort will help homeowners engage proactively and confidently in expanding the supply of affordable housing, starting in their own backyard.

At their informational gathering in the church parking lot, the City Systems team made the possibility of developing accessory dwelling units more ATTRACTIVE by having a model unit on display for homeowners to see and explore first-hand. Developing a more streamlined permitting process and templates added to the attractiveness of navigating an historically otherwise complicated permitting system.

San Mateo County’s messaging aimed at white, wealthy homeowners speaks to the power of communications and marketing DEFAULTS to instigate behavior change. Once City Systems developed communications and marketing featuring established defaults that resonated with people in East Palo Alto, there was more robust attendance at informational sessions on the part of homeowners from that community.

Finally, Derek’s sentiment that his team—and our society more broadly—must learn to communicate in ways that incite empathy speaks to the potential power of appealing to emotions or AFFECT when seeking to change behavior.For more information on City Systems’ inspiring behavior change work in East Palo Alto, please visit the City Systems East Palo Alto project page.

The theoretical basis for the Behavior Change Blog Series is informed by two mnemonic frameworks shown in detail below. The MINDSPACE framework is a list of the elements that inform cognitive biases and human behaviors, while the EAST framework is a list of directives that are derived from MINDSPACE and help inform strategies for influencing behavior change in humans. These two frameworks were established by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), a social enterprise based in the United Kingdom.

| MINDSPACE Framework | EAST Framework |

| Messenger – We are heavily influenced by who communicates information to us. | Make it Easy – Harness the power of defaults, reduce the ‘hassle factor’, simplify messages. |

| Incentives – Our response to incentives is shaped by predictable mental shortcuts such as reference points, aversion to losses, and overweighting of small probabilities. | Make it Attractive – Draw people toward preferred behaviors, design rewards and sanctions to maximize effect. |

| Norms – We are strongly influenced by what others do. | Make it Social – Show people the norm, use the power of networks to encourage and support, encourage people to make a commitment. |

| Defaults – We “go with the flow” of pre-set options. | Make it Timely – Prompt people when they are most likely to be receptive, consider immediate costs and benefits, help people plan their response. |

| Salience – Our attention is drawn to what is novel and also to what seems relevant to us. | |

| Priming – We are often influenced by subconscious cues. | |

| Affect – Our emotional associations can powerfully shape our actions. | |

| Commitments – We seek to be consistent with our public promises, and to reciprocate acts. | |

| Ego – We act in ways that make us feel better about ourselves. |

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

0 Comments