We Need to Manage Flood Risk

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

Now is a good time to rethink the way we manage flood risk. Or more accurately, perhaps now it’s time to actually manage flood risk.

At the heart of the American system of dealing with floods is the misguided idea that we can manage floods. Regardless of how many times catastrophic floods occur, the American public remains entrenched in one of the four stages of denial:

- It’s not going to happen.

- If it is going to happen, it’s not going to happen to me.

- If it is going to happen to me, it won’t be that bad.

- If it is going to be bad, I can deal with it.

Even though many elected officials know better, they, too, often choose to remain in denial, continuing to avoid the difficult decisions to increase spending and hence raise taxes (“not in my term of office,” NIMTOF), ignoring the long-term consequences and choosing to put flood risk management in the “too hard” column. They are not to be blamed: with our current Federal disaster assistance program, it can be a prudent gamble.

What if we stopped trying to manage floods and instead worked to manage flood risks? What if we viewed floods in terms of “losses avoided”? What if communities viewed effective flood risk management not a loss to be feared, but as an asset to be marketed? We might recognize flood losses for what they are: not single events, but compound processes that must be understood historically and from multiple viewpoints.

It’s not a novel concept. Many corporations today consider active risk management an asset and a central part of the strategic management of their organization. Corporations have a Risk Manager who reports directly to the CEO. Risk Managers identify, analyze, assess, control, avoid, minimize, or eliminate unacceptable risks. In doing so, they actively manage their portfolio of risk by using risk avoidance, risk retention, risk transfer, or a combination of these strategies. Most large government agencies also have a Risk Manager who routinely negotiates insurance contracts and works department heads to develop risk reduction strategies.

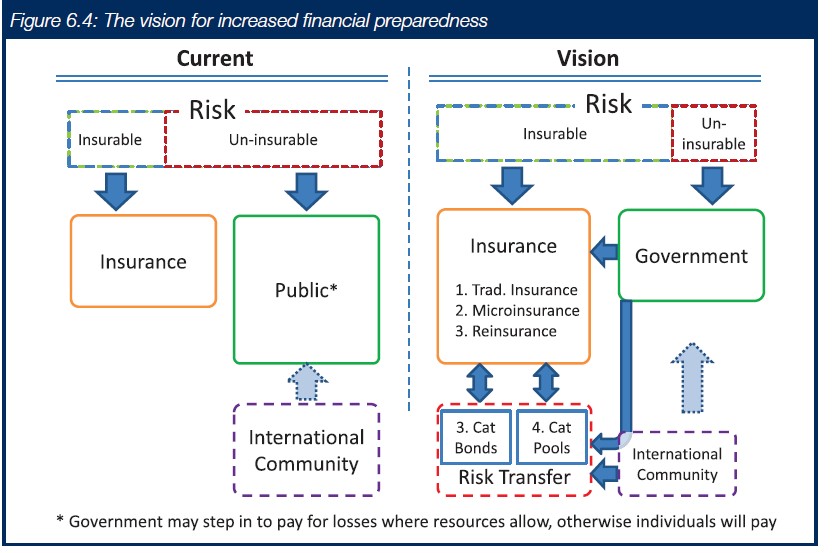

In 2011, the World Economic Forum(WEF) proposed just such a plan. In their white paper, A Vision for Managing Natural Disaster Risk, they outlined a plan for actively managing flood risk. The plan proposes to make more of the natural disaster risk insurable by utilizing risk transfer mechanisms and public-private cooperation. Their vision seeks to lessen the burden on individuals and governments by placing more of the risk with re/insurers and global capital markets who are well-equipped to actively manage these risks. They sum up this vision using the diagram below:

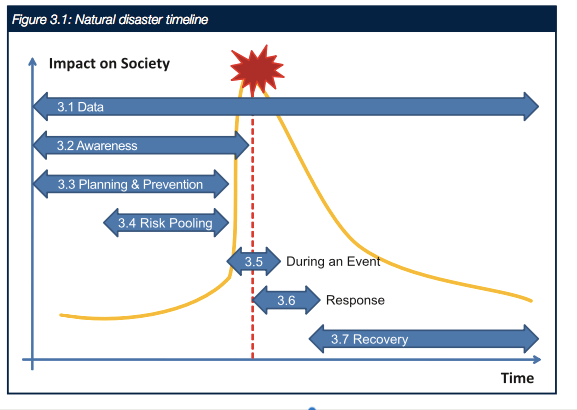

Following the WEF plan, we would start to view disaster risk reduction not as a discrete event, but as a timeline of events, beginning with preparedness, moving through the event and ending with recovery.

We would recognize that, for decision makers, adopting a compressive risk management approach that strikes the right balance between disaster prevention and risk transfer is challenging. It must be embedded in a broader strategy of economic growth and development, and it must be coordinated at all levels of government.

To meet this challenge, we would need to create a new government or quasi-government position, that of Watershed Risk Manager. A Watershed Risk Manger would report directly to the public oversight body and would be the natural focal point for the engagement of other stakeholders. Their responsibilities would include the inception, design, implementation and operation of the watershed risk-management program. They would be joined by a team with engineering, finance, insurance, and media expertise. Watersheds come in many different sizes. Thus, the scale of the area managed by the Watershed Risk manager would vary greatly. The watershed should be large enough to allow for landscape scale land use decisions, but small enough that local stakeholders feel they have a say in the decision-making process.

A key tool in the Watershed Risk Manager’s toolbox is the watershed catastrophe model. Catastrophe Models attempt to represent the likely direct impact of natural hazards on a portfolio of physical assets at risk, providing outputs that decision makers can use to inform risk management strategies. Catastrophe models combine information on hazards, exposure and vulnerability to estimate event-by-event losses.

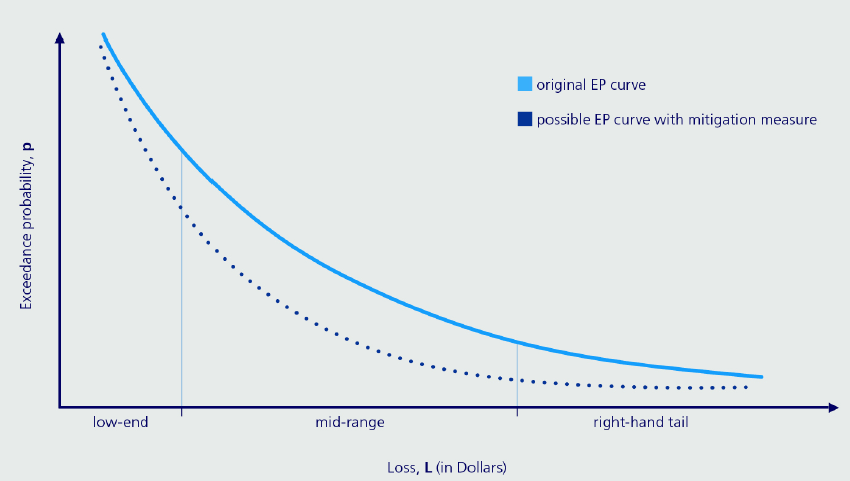

The output of a catastrophe model is an exceedance probability (EP) curve. The area under the curve is Average Annual Loss (AAL). These outputs can be used to inform a Disaster Risk Reduction Strategy.

For example, the area to the left side of the curve describes the expected losses associated with high-probability, low-end dollar value losses. This area of flood risk might be managed by a robust program of green infrastructure and just-in-time mitigation measures. A Cat model can capture the reductions in risk, demonstrating the value of green infrastructure and the value of not paving over grassland areas.

The right side of the EP curve describes the economic consequences of low-probability, high-consequence events—the Hurricane Harvey’s. These events might be managed by using risk transfer. In particular, they might be managed through the purchase of a disaster bond, such as a Catastrophe Bond or Cat Bond. Should a triggering event occur, the proceeds of the Cat Bond would be available quickly to help the community get back on their feet. Much like other bonds, disaster bonds are tax-exempt debt instruments that move private sector money into communities recovering from hurricanes, floods, or other calamities. In the past, the economic losses of low-probability, high-consequence events have been borne by Federal and State governments. As these funds are stretched thin, the degree to which the Federal government should be responsible for unwise local land use decisions is increasingly being called into question.

Using the EP curve, a community might justify taking the additional step of acquiring a resilience bond. A resilience bond links insurance coverage that public sector entities purchase with capital investments in flood-reducing infrastructure systems, such as flood barriers

The Watershed Risk Manager would be responsible for developing the estimates of the direct and indirect costs of these low-probability, high-consequence events and for negotiating the insurance instruments.

In the middle of the exceedance probability curve lies the opportunity to accept, mitigate, or transfer the flood risk. This is where the Watershed Risk Manager would add value. The Risk Manger would work with engineers, bankers, insurance professionals, and communications specialists to develop a robust suite of options.

One of the options might include a community-based parametric flood insurance program. Carolyn Kousky and Leonard Shabman from Resources for the Future present the outline for a community-based flood insurance program. Community flood insurance is a single policy, purchased by a local governmental or quasi-governmental body, that provides coverage to a large group of properties. A community insurance program could be based on the principles of parametric insurance to reduce costs—savings which could be passed on to the community or used to invest in flood risk reduction measures.

Unlike a traditional NFIP flood insurance program, a parametric insurance product is one in which the claims are paid based on a predefined triggering event. Two challenges with implementing a parametric insurance program center around agreeing on the payout and on the triggering event. However, these challenges are easily overcome with detailed catastrophe modeling and with a robust array of sensors or stream gages.

A community-based flood insurance program developed as a collaboration between engineers, insurance professionals, investors, and media professionals could:

- utilize the detailed flood risk information developed by engineers, thus reducing costs

- provide the specific form of coverage desired by the citizens

- permit the community to accept some degree of risk, passing the savings on to their citizens

- support an open and informed decision-making process.

An examination of NFIP policies paid by homeowners in California since 1994 finds that NFIP damage payouts in California have totaled just 14% of premiums collected. Compare this figure to 560% for the biggest recipient state, Mississippi. If California had invested in a statewide community-based insurance program, more than $3 billion would have been available to invest in flood risk reduction measures.

California has unparalleled expertise and a culture of progressive solutions for managing its flood risk. With the US NFIP facing an uncertain future – more than $20 billion in debt – my colleagues at UC Davis and I recommend a careful look at California’s place in the NFIP.

“In particular, California should now explore a state flood insurance program, with savings invested in long-term risk reduction. Properly implemented, a state-based insurance program and proactive flood mitigation strategies could synergistically benefit the environment, agriculture, recreation, and water resources. This approach has major challenges, with implications both for California and nationwide that should be explored.” (California Water Blog, December 14, 2016)

A state-led, community-based flood risk management program following the guidelines outlined by the World Economic Forum could leverage the robust economic muscle of the private sector.

Now is the perfect time to explore new ideas for managing flood risk. The NFIP will be up for reauthorization in December and tough choices will need to be made. As we have done with many other challenges, perhaps now is the time for California to lead the way in embracing and actively managing our flood risks.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

To my understanding, flood zone maps have not been updated since 1980 (?). We now have the ability to use drones to updates these maps. We may not be willing to spend money taking care of our infrastructure, but it’s relatively inexpensive to update flood zone maps using drones, big data, and machine learning. Empower people to make informed decisions about where they live, invest, and buy insurance.

Since billions of taxpayers dollars are repetitively directed into disaster response & recovery, somehow we need to “inspire” those with authority to consider comprehensive reform of the NFIP. As I’ve laid out many times before, all 3 legs of the Program desparately need reform. To date, attempts to raise premiums, writing & rewriting of compliance guidance, and digitization of old maps have been the meat of reform and, obviously, it’s far from being enough.

Water movement by mechanical means can shift water to areas less flooded controlling flood waters rather than just letting gravity win. A four guideway system can move 103.5 million gallons per day away from a flood predicted area. Floods do have a wide dynamic range of flows so this mechanical solution has limitations obviously but a few inches of water in your home or a few inches from your front step make a huge difference in damage claims. Moving water out ahead of areas of rainfall may be how we can cope with some potential floods. It does require pro-actively starting the construction of this transportation system a year before a flood.

Thanks so much for this Kathy. A wonderful synopsis of where we are and where we need to go. Who needs to put pressure on the rethinking of NFIP at the state level? The Governor’s Office? Who are the main stakeholders that need to engage in this process to move to a state flood insurance program?