4 Ways Civic Organizations Can Use Media to Build Trust

Who will you meet?

Cities are innovating, companies are pivoting, and start-ups are growing. Like you, every urban practitioner has a remarkable story of insight and challenge from the past year.

Meet these peers and discuss the future of cities in the new Meeting of the Minds Executive Cohort Program. Replace boring virtual summits with facilitated, online, small-group discussions where you can make real connections with extraordinary, like-minded people.

We are working to understand how organizations using media and technology to build trust, can do so in this age of misinformation, fake news, and distrust. How can public serving organizations (government, news, and community groups) build trust with their constituents in a context of increasing distrust? Can novel communication technologies help? What about more savvy uses of data? When people share false news stories on their Facebook feeds because they want to believe it’s true, and when political figures cast doubt on reputable news stories because they want to believe it’s untrue, how should well intentioned organizations create and share information if they want to establish trust with publics?

In this climate of distrust, we conducted a study to learn how activists and civic institutions are leveraging media and digital technology to rebuild and reimagine new approaches to civic discourse and action. Through our conversations with over 40 practitioners in Boston, Chicago, and Oakland, we provide a way of identifying and evaluating media and technology designed to facilitate democratic process. The full report is available here.

Prioritizing the Social in Media

We spoke to people in a variety of civic organizations (everything from government, arts, to community journalism), who were grappling with the challenge of using new media and technology to engage, or connect with the publics they serve. Among these practitioners, we saw that their work reflected an ethic of care, an essential part of citizenship that orients people towards an understanding that citizenship is the practice of how we work with others to take care of the world we live in.

The emphasis on building relationships also reflects the design value of meaningful inefficiencies, where the use of technology and media for purposes of organizing is not intended to create a streamlined and prescriptive approach to solving civic challenges, but is instead meant to encourage collaboration, socializing, and problem solving that go beyond the imagination of what the designer intended.

These two values sit at the core of of how we came to define the work of those we interviewed as civic media practice. Simply put, civic media practice is the work of making media and technology that supports democratic process. Read on in this post to learn about what that actually means in practice.

Civic Media Takes Time

How practitioners move from adopting novel technologies to assuring shared goals and mutually beneficial outcomes is central to civic media practice. In the current climate, it was not acceptable for people to design a communication strategy in a vacuum. They understood that doing so would run counter to goals of building trust. Using technology was not a silver bullet solution to solving organizational problems; it required careful negotiation and facilitation, much like any project premised on strong relationships.

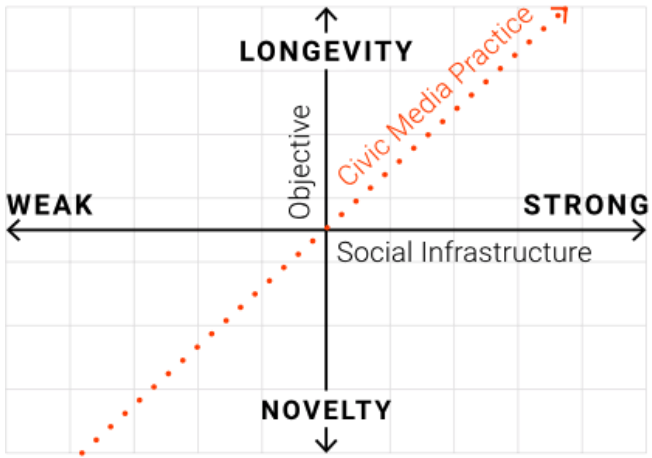

As such, civic media always takes place over time. In this graph, we provide a method of plotting a snapshot of a project along two dimensions: the horizontal of social infrastructure and the vertical of objective.

Social infrastructure is defined as the “people, places, and institutions that foster cohesion and support.” If a group has strong existing relationships with a community, they will be on the right side of the plot. If they are brand new to a community, they will be on the left.

Civic media practice takes place over time and across two dimensions.

The second dimension of civic media practice is the objective — how practitioners think about the impact of their work (i.e. impact in the short-term or long-term). Some projects are designed with novelty in mind (i.e. a social media campaign designed to garner quick attention), and some with longevity in mind (i.e. a publicly designed mural on a community center).

The Four Activities of Civic Media

What defines civic media practice, distinct from other forms of media practice, are a set of four activities that characterize this striving towards the top right quadrant in the graph. Practitioners work to situate themselves within a network of stakeholders with shared interests, and have made long-term impact a core objective in their work. The work of practitioners doesn’t need to begin there, but it needs to aspire towards it. The four activities include:

1. Network Building

Civic media practitioners place a premium on convening people as part of their practice. They often place value on informal gathering spaces that bypass some of the strictures of formal meetings or input sessions.

2. Holding Space for Discussion

The work of striving for common good in making civic media involves defining a shared set of values. Our research reveals that this is supported by holding space for discussion. Practitioners do this by regularly engaging a variety of stakeholders and doing the work required to assure that all voices are heard and there is ample room for dissent.

3. Distributing Ownership

This describes the work of building capacity of communities to continue the work once the project has concluded. In our study, the work of distributing ownership appeared when practitioners outline clear pathways to participation, actively encouraging a power dynamic where stakeholders take the reins of the practice, or when practitioners adopt an open source ethos to their work, sharing knowledge and encouraging appropriation and repurposing of practice.

4. Persistent Input

Practitioners understand the context of their issues by not simply asking people what they think, but doing so from a position of stability, continuity, and trust: asking once, and then being in the same place to ask again. This persistence is reflected in long-term relationships between practitioners and the communities they work in. This practice of understanding the problem through persistent relationships is not only what motivates the design of a particular story or project, it is the value driving the entire practice.

Measuring progress

In the report we argue that practitioners creating and deploying media and technology for civic aims need to turn their attention to process over outcome. We offer a series of questions to encourage reflection as practitioners progress along the axes of social infrastructure and objective.

The first step is to plot the starting point for a project. This requires assessing social infrastructure. Here, practitioners can consider what level of connection they have with the real or perceived end users, how strong their current relationships with stakeholders are, and if or for how long they have worked with the target community.

The assessment of objective is based on intention. Practitioners can ask if their project is intended to be short-lived or long-term or if the media or technology developed will remain in the community for an extended period of time.

With the starting point in place, practitioners can set up regular intervals throughout the project lifespan to see how their project is moving along the graph. Doing so can be done by asking questions related to the four activities:

Network building:

Have you developed new connections in the community you’re working in?

Holding space for discussion:

Are you taking steps to engage people outside of your immediate network?

Distributing ownership:

Are you creating opportunities for stewardship by stakeholders?

Persistent input:

Are you engaged in long term conversations with stakeholders?

What else is in the report?

In addition to providing more detail around the activities and measurement of civic media practice, we also provide two case studies from our research. We apply our process of measurement to each case to demonstrate how civic media practitioners moved their projects towards the top right quadrant of the graph, emphasizing longevity and strong social infrastructure in their work.

We are currently working to develop “reflective practice guides” for a range of practitioners. Beginning with journalists and government employees, we are creating instruments to put the evaluation framework into practice. Please contact eric_gordon@emerson.edu to learn more.

Discussion

Leave your comment below, or reply to others.

Please note that this comment section is for thoughtful, on-topic discussions. Admin approval is required for all comments. Your comment may be edited if it contains grammatical errors. Low effort, self-promotional, or impolite comments will be deleted.

Read more from MeetingoftheMinds.org

Spotlighting innovations in urban sustainability and connected technology

Middle-Mile Networks: The Middleman of Internet Connectivity

The development of public, open-access middle mile infrastructure can expand internet networks closer to unserved and underserved communities while offering equal opportunity for ISPs to link cost effectively to last mile infrastructure. This strategy would connect more Americans to high-speed internet while also driving down prices by increasing competition among local ISPs.

In addition to potentially helping narrow the digital divide, middle mile infrastructure would also provide backup options for networks if one connection pathway fails, and it would help support regional economic development by connecting businesses.

Wildfire Risk Reduction: Connecting the Dots

One of the most visceral manifestations of the combined problems of urbanization and climate change are the enormous wildfires that engulf areas of the American West. Fire behavior itself is now changing. Over 120 years of well-intentioned fire suppression have created huge reserves of fuel which, when combined with warmer temperatures and drought-dried landscapes, create unstoppable fires that spread with extreme speed, jump fire-breaks, level entire towns, take lives and destroy hundreds of thousands of acres, even in landscapes that are conditioned to employ fire as part of their reproductive cycle.

ARISE-US recently held a very successful symposium, “Wildfire Risk Reduction – Connecting the Dots” for wildfire stakeholders – insurers, US Forest Service, engineers, fire awareness NGOs and others – to discuss the issues and their possible solutions. This article sets out some of the major points to emerge.

Innovating Our Way Out of Crisis

Whether deep freezes in Texas, wildfires in California, hurricanes along the Gulf Coast, or any other calamity, our innovations today will build the reliable, resilient, equitable, and prosperous grid tomorrow. Innovation, in short, combines the dream of what’s possible with the pragmatism of what’s practical. That’s the big-idea, hard-reality approach that helped transform Texas into the world’s energy powerhouse — from oil and gas to zero-emissions wind, sun, and, soon, geothermal.

It’s time to make the production and consumption of energy faster, smarter, cleaner, more resilient, and more efficient. Business leaders, political leaders, the energy sector, and savvy citizens have the power to put investment and practices in place that support a robust energy innovation ecosystem. So, saddle up.

0 Comments